After our three exciting days in Cappadocia, we were driven back to Kayseri Airport for a flight back to Istanbul. As there is no direct flight from Kayseri to Pamukkale, this was the quickest and most convenient route to the next stop on our tour of Turkey. We had decided that there were a number of places around Pamukkale to see so we booked a hotel for two nights. Many tourists bus in from Izmir or Selcuk on the coast and this takes about three hours. Unless you book a hotel, it makes for a very tiring day

Pamukkale is a famous tourist name that attracts large numbers of travellers to visit its hot springs and the amazing travertine slopes that flow down its mountain. Driving there from the airport, from a distance I thought I was approaching a ski resort given as that was the only type of ‘white’ mountain I had ever encountered before. However, this didn’t make sense in Turkey’s hot summer so I realised I was looking at slopes covered by travertine, a rock produced by carbonate minerals dissolved in flowing water and then deposited on the side of the mountain.

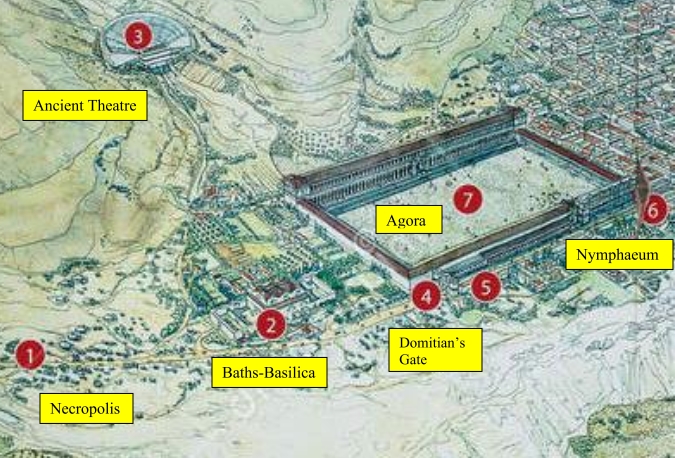

In Turkish, the name ‘Pamukkale’ means ‘cotton castle’. However, for me the point of visiting this famous spa centre was that sitting on top of the mountain behind the travertine slopes was the remains of an ancient city that had begun with the Phrygians who were a bronze age culture from the Balkans who migrated to Anatolia. The ruins that can be visited here are mainly Roman ruins; the name of this city is Hierapolis, meaning ‘Holy City’.The image above left shows that parts of the Roman ruins being overtaken by the travertine flows. I got the impression that the bulk of tourists come for the sparkling slopes and the rock pools, rather than these Roman Ruins.

We had booked a guide for the next day and as we had collected a hire car, we were able to meet him at a shopping area that was close to the northern gateway to the Pamukkale/Hierapolis site. This enabled us to walk from the start of Hierapolis and make our way towards the travertine slopes at the other end of the complex. Our guide on this day was a very informative an interesting man whose guide income supplemented his wages as a university tutor. One of the personal discussions we had with him was about the increasing Islamization of Turkey that we had noticed since a previous visit; particularly the number of women in the streets wearing hijabs in public as opposed to western dress that had been very common in places like Istanbul a few years before. He explained that he felt the pressure in his University teaching to be careful of his words, to ensure that he maintained his job. Our visit to Turkey was in 2013 and three years later there was an attempted coup in Turkey by a faction from the Turkish armed forces. In the purge that followed, 15,000 teachers, and every university dean in the country lost their jobs. Ever since then, we have always wondered what happened to our friendly, informative guide from that day.

The site of Hierapolis, like all ancient archaeological sites, is a complicated walk-through due to the different ages of the ruins and the differing states of building preservation. Anatolian cities and towns early in the first century CE were subject to destructive earthquakes. In 17 CE and 60 CE, this city was ruined by earthquakes and on both occasions had to be rebuilt.

The first section we entered as shown on the map above was an ancient cemetery (necropolis) outside the main gates of the city and there were plenty of examples of impressive tombs in various degrees of preservation. Hieropolis was a logically planned city based on a grid pattern that bordered the edge of the ‘Cotton Castle’. The entrance to Hierapolis is called Domitian’s Gate built by Julius Frontinus (proconsul of Asia around 82-83) and the city’s main street took us all the way down to the mineral springs and ‘Great Baths’ that were part of the attraction of this spa town for its Roman occupiers.

From this section of the site-map of Hierapolis, the main places of note in the first section of the city are listed. It shows that before you reach the Gate of Domitian, there is a huge, fenced off building that looked to be struggling with imminent collapse. It is referred to as the Bath-Basilica. It was originally built as a Bath House by the Romans in the third century CE and then rebuilt as a church basilica in the fourth century when the city was becoming Christian. If the Basilica was struggling to remain standing, the remnants of the original theatre of Hierapolis on the neighbouring hillside has nearly completed its transition back into the slopes. It was destroyed by an earthquake in the early Roman period and was replaced by a larger theatre on the slope above the southern end of the city.

Central to the survival of a large Roman city is the water supply. The building referred to as the Nyphaeum is a second century building dedicated to the water spirits, the Nymphs, and its purpose was to distribute water to the houses of the city. It needed repair by the fifth century during the Byzantine era.

The Main or Frontinus Street continues on past the remains of the old agora (meeting/market square) and the Nymphaeum.

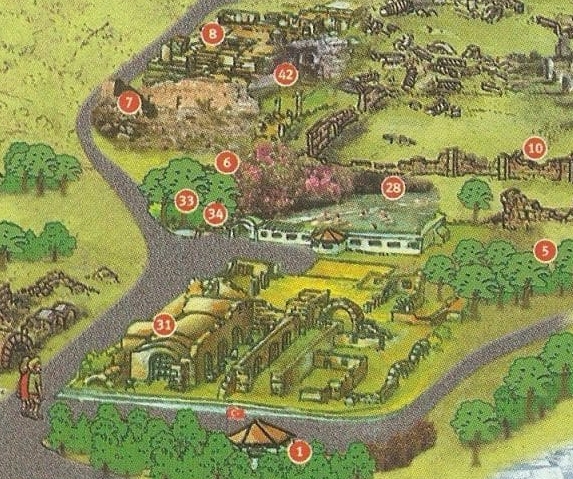

Not indicated on the map to the left is the Martyrium of St Philip which can be seen further up the slope from the limited remains of the old theatre. For those interested in the rise of Christianity, St Philip is an interesting case. He is mentioned a number of times in the Gospels asking Jesus some thoughtful, probing questions. It has been suggested that he left the other apostles in Jerusalem after the crucifixion and travelled to Phrygia and there are quite a number of references to Philip living in Hierapolis in early accounts. Like St Peter in Rome, Philip is said to have been crucified upside down for the crime of converting the proconsul’s wife to Christianity. In 2011, archaeologists found a grave near the martyrium that they believe to be St Phillip’s. The Martyrium was built around the early 5th century CE and only lasted until the start of the sixth century when it was burnt down.

Further across the slopes at site #12 can be seen the significant remains of the Roman theatre. It was built in the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian around 60 CE and as can be seen in the photos below, there are significant remains of the theatre’s façade and attached sculptural reliefs. The solid construction of this theatre meant that it survived earthquakes until the 7th century when it couldn’t escape the collapse that was city wide. It is believed that after this time, Hierapolis was gradually abandoned.

Just down the hill from the Roman Theatre is the area of the Hierapolis site that contains the elements of this landscape that most likely brought about the original settlement to be built here and why subsequent people continued to make their home around this mountain. Like the famous Temple of Apollo in Delphi, this centre was built over a geologically active fault and there was a cave on this spot that was dedicated to an Earth Mother Goddess, Cybele, who is the only known Phrygian Goddess that has come down to us from the archaeological record. Her acolytes would enter the cave that emitted carbon dioxide and by holding their breath, did not die from the noxious gases. Like the priests in Delphi, their predictions for the future would then to be trusted as accurate.

At the site on the map above marked #8 was built the Temple to Apollo who was the town’s principal God before the arrival of the Romans. Only the foundations of the temple remain today having suffered the same cycle of construction, destruction by earthquake and reconstruction in the third century. Beside the temple at #42 is the Plutonion which was where the prophetic priests of Apollo went down into the cave and were not overpowered by the noxious fumes that were emitted here. It is the presence of this geological activity that meant the waters that flowed above ground into the thermal pools of the area made Hierapolis a famous attraction for Romans seeking cures for all manner of health issues. If you come prepared with swimming gear today, you can, for a price, swim in the hot pool (#28 on map above) as the photo on the left shows. This is a poor-quality phone photo I took of my fellow tourists enjoying the health-giving waters as well as swimming among stone remnants of ancient Hierapolis. It is probably natural that the largest building of Hierapolis, the bath house, was built on this site near the thermal pools.

The cycles of changing religious belief over the millennia are illustrated at many sites around Turkey. For example, at this site where the underground waters and noxious gases came to the surface was an important shrine to older religious beliefs of Anatolia until the start of the fourth century. When Christianity became the dominant religion in Hierapolis in the fourth century, the cave of the Plutonion was filled with rocks and so those looking for predictions for their futures were shut out of this prophetic landscape.

In 1984, the huge Roman bath house was restored and became the onsite museum displaying many of the artifacts rescued from the grounds of Hierapolis and neighbouring towns. The image below of two sarcophagi in the museum illustrates the quality of the displays as well as the amazing stone-work of the original Roman bathhouse.

Hierapolis and Pamukkale have been declared World Heritage Sites and the extract below from the UNESCO website makes a great summary of the importance of this wonderful ancient city and its environs.

Outstanding Universal Value…Brief synthesis

Deriving from springs in a cliff almost 200 m high overlooking the plain of Cürüksu in south-west Turkey, calcite-laden waters have created an unreal landscape, made up of mineral forests, petrified waterfalls and a series of terraced basins given the name of Pamukkale (Cotton Palace). Located in the province of Denizli, this extraordinary landscape was a focus of interest for visitors to the nearby Hellenistic spa town of Hierapolis, founded by the Attalid kings of Pergamom at the end of the 2nd century B.C., at the site of an ancient cult. Its hot springs were also used for scouring and drying wool. Ceded to Rome in 133 B.C., Hierapolis flourished, reaching its peak of importance in the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., having been destroyed by an earthquake in 60 A.D. and rebuilt. Remains of the Greco-Roman period include baths, temple ruins, a monumental arch, a nymphaeum, a necropolis and a theatre.