A visit to Saint Mark’s Square is usually the highlight of any visit to Venice. It is considered the most important square in Venice and has been the centre of Venetian History since the early ninth century when the first church was built here about 819 CE. For the purists, there are in fact two squares in this area; the open space in front of the basilica stretching all the way to the western end is referred to as Piazza San Marco and the area in front of the Doge’s Palace is the Piazzetta.

Apart from the main buildings, there are many smaller treasures to investigate in St Mark’s Square and a commercial tour of this iconic place is probably the best way to get the most out of a visit here. This blog will canvas just some of the main features to keep an eye out for.

When walking to St Mark’s Square, the route many visitors take approaches through the narrow alleyways from the Rialto Bridge and if you wander too far to the left, you emerge on the Grand Canal via the fish market. If you find the street named Mercerie to the right of the Rialto Bridge and follow it faithfully towards the Grand Canal, you emerge in Piazza San Marco directly at the corner of the basilica. The sight of this beautiful, very ornate building is a highlight of visiting Venice.

The image to the right is the central archway of the façade of the Basilica and apart from the many sculptures holds two key images. One is the golden lion of Venice that takes pride of place at the top, centre of the archway. The second grand image is of the four horses of St Mark that stand at the edge of the central archway. These are not just any horse sculptures. Before their time in Venice, they were known as the Horses of the Hippodrome of Constantinople. If you visit the hippodrome in Istanbul today, you will see the plinths that these horses once stood upon until this eastern Roman city was looted as part of the Fourth Crusade in 1204. However it is believed these horses date from the 2nd or 3rd century CE and are of classical Greek origin. They represent an amazing time capsule of the last two millennia.

The four horses are too valuable to stand out in the weather of Venice through all the seasons. The four we see on the façade of the Basilica are copies. The other four are inside the building, not far from the external wall where the copies stand outside. To the left is an image of the original four horses.

One of the predictable events of Napoleon’s invasion of Venice was the removal of the horses from the Basilica and their shipment to the Louvre in Paris in 1797. They were returned in 1815. (I have always wondered why they weren’t shipped back to Istanbul’s hippodrome on this occasion!)

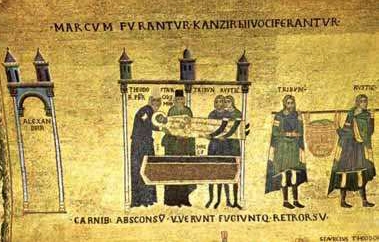

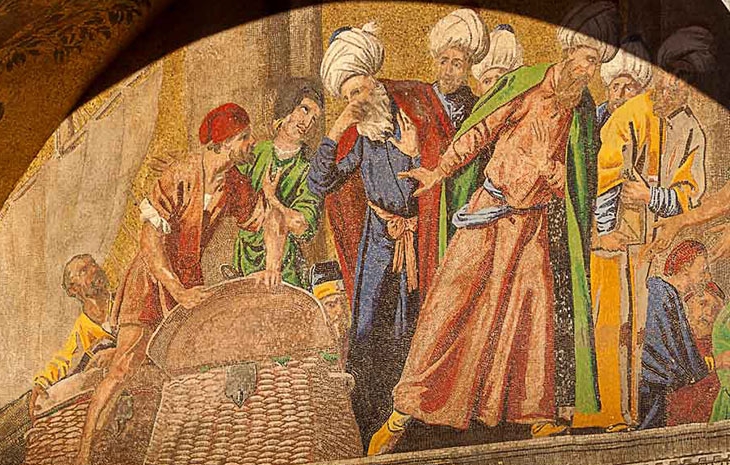

The story of the construction of a church on this site is based around the story of the theft of the body of St Mark the evangelist from a church in Alexandria, Egypt. A short version of the story is that a pair of merchants stole the body of St Mark, hid it in a weaved basket underneath pig meat and shipped it from Alexandria to Venice. The current basilica is the third version of the church built on this site and today the casket of St Mark is kept under the high altar. In the first archways of the basilica, the curious story of the theft of St Mark’s, thousand year old body is presented in mosaic form and its arrival in Venice is also presented here. One of the ageing clerics appears to be holding his nose in the image to the right below; presumably it is the pig meat that smells, not the ancient body. The image above right is almost a cartoon version of the theft of St Mark and is to be found in the Chapel of Saint Clement inside the Basilica.

A visit inside the Basilica is always a splendid event and I was lucky enough to do so on a 2004 visit. I have returned to Venice twice since that time and the long queues for entry into the Basilica and the Doge’s Palace have always put me off repeating this visit. The extended wait in the queue is probably worth it for the first-time visitor.

As visitors arrive in the square via Merceria, the Basilica is an overwhelming view. If visitors don’t turn around and inspect the archway that they have just come through, they will miss the impressive clock tower that was built in the 1490s. This clock tower was placed at this spot so that it could be seen by ships arriving via the lagoon and would be suitably impressed by the wealth of Venice.

At the very top of the tower can be seen a bell and two figires who strike the bell on the hour. The next stage down is the winged lion of St Mark in front of an open book. Originally there was a statue of one of the Doges kneeling before the lion to the right. The invading French army, as was their want, decided to remove the statue of the Doge as it was a key symbol of the old regime of Venice. (It hasn’t been restored!) The next stage down shows the virgin and child plus two panels revealing the current time. Above the archway is the final stage of the tower showing the great clock face. Inside the marble circle are the 24 hours of the day and in a further inner circle there are the signs of the Zodiac. The whole assembly of the tower is an amazingly complex piece of engineering.

At the very top of the tower can be seen a bell and two figires who strike the gong on the hour. The next stage down is the winged lion of St Mark in front of an open book. Originally there was a statue of one of the Doges kneeling before the lion to the right. The invading French army, as was their want, decided to remove the statue of the Doge as it was a key symbol of the old regime of Venice. (It hasn’t been restored!) The next stage down shows the virgin and child plus two panels revealing the current time. Above the archway is the final stage of the tower showing the great clock face. Inside the marble circle are the 24 hours of the day and in a further inner circle there are the signs of the Zodiac. The whole assembly of the tower is an amazingly complex piece of engineering.

The Doge’s Palace was not built for another five centuries after the construction of St Mark’s Basilica. It was built in 1340 and like all the major buildings of Venice, was extended and modified in the following centuries. There was an earlier building here where the Doges led the government of Venice but little trace of this building remains. I visited this palazzo in 2004 and was very impressed by the statues, stairways and highly ornate rooms where huge paintings of past battles seemed to be the go for the decorations of the walls. The palazzo became a museum in 1923.

The Doge’s Palace is a huge, complex building and institution and there is much to see here for those who have the time and patience. One of the features of the Palace that has many visitors interested is in its function not only as a governmental building in Venice but it was also a prison for centuries, beginning in this role not long after the palazzo was built. Its most famous prisoner is Giacomo Casanova who was arrested in 1775 for “affront to religion and common decency” and held in the top wing of this palace. He eventually escaped and his escapades were recorded in his autobiography, Histoire de ma Vie.

Casanova’s prison wing was reached over the fully enclosed Bridge of Sighs and today this prison bridge is a favourite ‘sight’ round the corner of St Mark’s Piazzetta. Folk hurrying to catch a ferry from San Zacarria have to jostle with the crowd on Ponte della Paglia which crosses the canal at the back of the Doge’s Palace; for some reason that story of the famous lover escaping from prison requires a lot of attention from the many visitors gazing at the Bridge of Sighs and the canal it crosses.

Close to the edge of the Grand Canal there are two marble and granite pillars that have statues of the patron Saints of Venice on top. In the photo to the right, the symbol of St Mark, the winged lion, sits on top of the left-hand column. The figures on top of the column to the right consist of the city’s first protector, St Todaro. He is a saint from the Byzantine tradition and stands holding a spear placed on top of a dragon which he has just vanquished.

Like so much of early Venetian history, the arrival date of the columns is uncertain, probably sometime around the 11/12th centuries. They may have been brought from Constantinople or Tyre in Lebanon and because of their weight, they were left lying on the quay for many years. Bringing these columns to Venice by sea was a major production, somewhat like the process that the Romans had to develop to bring all the looted Egyptian obelisks to their Roman cities.

Not far back from the Grand Canal and the two pillars is the Campanile or bell-tower. Initially the bell-tower was to be part of a series of defensive walls on the edge of St Mark’s square back in the tenth century. After the initial construction, additions were made to it in the coming centuries. These earlier structures were made from wood and copper plates but as it was a target for lightning (and bonfires!), it regularly suffered from fire hazards. It was even damaged by an earthquake in 1511.

The wait for a complete reconstruction of this belfry/tower had to wait until 1902. The foundations of the tower had been deteriorating for many years and by 1902 there were signs that all was not well with the tower that was considered the oldest of its type surviving in the world. On Monday 14th July the square was evacuated as stones began to fall after 9.00am. At 9.53 the tower collapsed so I am sure photos were taken by on the spot reporters, alert to a major local story about to occur at the end of St Mark’s Piazzetta. The tower was completely rebuilt and was inaugurated in March 1912.

The Piazzetta San Marco is most definitely the most interesting section of the overall square. Piazza San Marco is obviously the largest area and it takes up the whole area surrounded by the three graceful buildings that are the walls of this piazza. These buildings contain cafes, museums of different forms, shops, a large library as well as the office of important city officials.

It is the West End of the Piazza that still has reminders of the long history of Venice. Given that this building is sometimes called the Napoleonic Wing, it becomes evident that Napoleon had plans for himself here before the tides of war turned against him in Europe. He was going to build himself a palace here with a great view of St Mark’s but all that’s left of this plan is the ceremonial staircase that was meant to lead up to his palace. It now leads to the Correr Museum.

APPENDIX 1…Interested in Opera…Where is La Fenice?

There is a passage through the western end of San Marco’s Piazza that links the visitor to the famous Venice Opera House, La Fenice, as per the map below.

If you have time on your hands, San Moise Church is on this route to the Opera House and the façade of this church (founded originally in the 8th century!) is worth a stop to take in its amazing complexity.